Top three first basemen in modern Orioles history:

- Eddie Murray (1977-1988, 1996)

- Boog Powell (1961-1974)

- Rafael Palmeiro (1994-1998)

Can't find a better man than Eddie

The Orioles have had some fine first basemen in their history, but the greatest of them all was indisputably Eddie Murray. Murray's achievements were recapped extensively last year upon his induction into the Hall of Fame, but here's a numerical refresher.

- Murray wasn't called Steady Eddie for nothing. In his first twelve seasons in Baltimore (1977-1988), he was amazingly consistent with the bat. He hit .277 or better every year, topping out at .316 in 1982. "Just Regular," as his gold necklace modestly proclaimed, produced regularly in the power department as well, hitting at least 25 doubles and 25 or more home runs in ten of those twelve years. The only exceptions were the strike-shortened 1981 season, when he was on pace to easily exceed those totals, and 1986, when he hit just 17 home runs in the only year in which he landed on the disabled list as an Oriole.

- Murray hit twenty or more homers in a season sixteen different times in his career, including nine straight from 1977-1985. He also hit .300 or better seven times and drove in 100 or more runs in six seasons. In fourteen years he hit at least .280, and he drove in 75 or more runs in each of his first twenty seasons.

- Murray's durability and consistent excellence helped him pile up formidable batting totals. In his 21-season career, he played 3,026 games (6th in MLB history) and recorded 3,255 hits (12th), 560 doubles (19th), 504 home runs (20th), and 1917 runs batted in (8th).

- As far as rate stats, Murray was very good, if not jaw-droppingly great: .287 batting average, .359 on-base percentage, and .476 slugging percentage for a .836 lifetime OPS. If those doesn't sound overly impressive, consider that roughly 85% of Murray's plate appearances came before the uptick in league offense that remains in effect today. So Murray's numbers need some context. According to Baseball-Reference.com, the league averages in Murray's career were .262/.328/.399 for a .727 OPS. Murray's lifetime adjusted OPS+ was 129—i.e., Murray's league- and park-adjusted OPS was 29 percent better than the average hitter's OPS in his time. Another measure, Clay Davenport's Equivalent Average, rates Murray's career batting output at .301, well above the league average of .260.

As an Oriole, Murray's totals are all over the offensive leaderboard as well:

Murray's Oriole batting totals and team ranks Category G AB H 2B HR R RBI BB Murray's total 1,884 7,075 2,080 363 343 1,084 1,224 884 Rank in O's history since 1954 4th 3rd 3rd 3rd 2nd 3rd 3rd 5th

Murray's Oriole batting rates and team ranks Category BA OBP SLG OPS OPS+ EqA Murray w/O's .294 .370 .498 .868 139 .311 Rank in O's history since 1954* 3rd 10th 5th 6th 4th 3rd *2000 or more PA's

- Murray was also renowned as a deadly clutch hitter. The splits compiled by Retrosheet (complete up to 1993) back up this perception: Murray's on-base percentage and slugging percentage rose significantly in his plate appearances with men on base and with runners in scoring position, and he was absolutely lethal with the bases loaded. His 19 lifetime grand slams trail only Lou Gehrig's 23 in baseball's annals.

- Not just a great hitter, Murray was also polished with the glove at first base. Bill James credited him with the most defensive Win Shares by a first baseman in his league five times: in 1979, 1981-1983, and 1989. The American League handed him its Gold Glove award from 1982-1984.

- Though not fast afoot, Murray stole 110 bases at better than a 70% clip in his career.

- Before receiving baseball's ultimate honor in Cooperstown last year, Murray was recognized with distinction in his own time. He won the American League's Rookie of the Year award in 1977, was selected to eight All-Star teams, finished in the top 10 in MVP voting eight times (including second place in 1982 and 1983), and took home three Silver Slugger trophies to match his three Gold Gloves. And seven times he was named the Most Valuable Oriole.

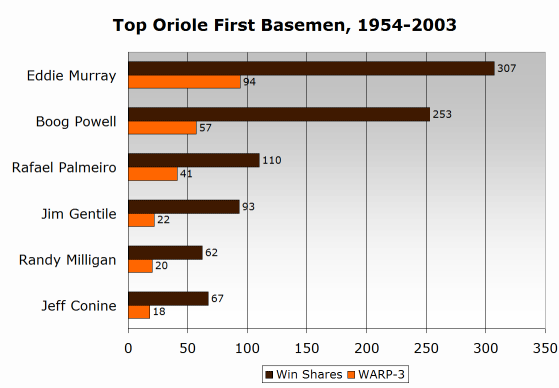

- All those numbers added up to 437 lifetime Win Shares, 307 of which he earned as an Oriole, and 127 career WARP-3, 94 of which came while wearing the orange and black.

Murray was more than just a man of great statistics, although those statistics tell a staggering story by themselves. Though he refused to talk to the press during his playing career, he was by all accounts a great teammate, a dedicated worker, and a smart player. Since his retirement in 1998 he has fashioned a respectable second act as bench coach for Baltimore (1998-2001) and hitting coach for Cleveland (2002-present).

Well done, Boog, well done

Boog Powell may be best known around Baltimore these days for his barbecue stand located on Eutaw Street just beyond the right-field wall at Camden Yards. But in his years manning first base for the Birds in the '60s and '70s, he served up plenty of big hits as well. His 253 Win Shares and 57 WARP-3 as a Bird place him securely in second place among Oriole first basemen.

Powell, in his best years, was just as devastating a hitter as Murray. His .606 slugging percentage in 1964 led the league, and he exceeded 30 home runs and 100 RBI in 1966, 1969, and 1970. Those 1970 numbers—35 HR, 114 RBI, .297/.412/.549—and the Orioles' success earned him the AL MVP trophy, after he was third in the '66 voting and runner-up in '69.

Powell hit the long ball and drew walks as well as any first baseman of his era save Harmon Killebrew. He didn't have Murray's consistency or durability; Powell's batting averages routinely vacillated between the .290s and the .250s, and his home run totals went from the thirties to the teens and back. Nor did he match Murray's fielding ability; although Powell had good hands, both James and Davenport rate his range as worse than the average first baseman. But he more than held his own as a player, compiling a .266/.361/.462 overall line (.266/.362/.465 with Baltimore) despite playing much of his career in the most run-starved period since the dead ball era. That translates to a lifetime 134 OPS+ and a .298 EqA. Here is how some of Powell's hitting stats stand in modern Oriole history:

| Category | G | AB | H | 2B | HR | R | RBI | BB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Powell's total | 1,763 | 5,912 | 1,574 | 243 | 303 | 796 | 1,063 | 889 |

| Rank in O's history since 1954 | 5th | 5th | 5th | 6th | 3rd | 5th | 4th | 3rd |

| Category | BA | OBP | SLG | OPS | OPS+ | EqA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Powell w/O's | .266 | .362 | .465 | .826 | 135 | .298 |

| Rank in O's history since 1954* | 17th | 13th | 7th | 8th | 6th | 9th |

*2000 or more PA's

Powell's bat faded as he crossed age 30, and he retired two years after being traded to Cleveland in 1975. But during his 13 seasons and change in Baltimore, he frequently rose to the occasion as a major component of four Bird pennant-winners. He definitely belongs among the Oriole greats.

Palmeiro: quietly spectacular

The career of Rafael Palmeiro is somewhat similar to Murray's in that he has accumulated formidable numbers by combining excellent performance and enviable durability while never enjoying a blockbuster, no-doubt-about-it MVP type of year. Now nearing 550 home runs and 3,000 hits, he is almost certainly destined for the Hall of Fame.

Upon signing his latest contract with the Birds last winter, Palmeiro said that he wanted to enter the Hall as an Oriole. This statement is a little surprising because he has played ten seasons for the Rangers, but 2004 is just his sixth in Baltimore. The preference probably comes from the greater concentration of winning experiences he enjoyed in Baltimore. Palmeiro's Texas clubs (1989-1993, 1999-2003) had a cumulative .491 winning percentage and reached the postseason just once, in 1999, when they were summarily bounced by the Yankees. That record pales in comparison to Palmeiro's first Oriole tour from 1994 to 1998, when the Orioles played to a .538 winning percentage and reached the American League Championship Series twice. (In truth, the discrepancy should have been even greater, as Texas outperformed its Pythagorean win expectation and Baltimore underperformed its expectation during the relevant years.) Palmeiro also expected to play multiple seasons in Baltimore to close out his career; his current deal is guaranteed only for 2004, but has options for 2005 and 2006. As of now, it appears that the Orioles will allow Palmeiro to go elsewhere next year.

Palmeiro's contributions to the Orioles in the 1990s (his 2004 stats do not count in this analysis since they came after the club's first 50 years) are representative of his outstanding career. In five seasons, he missed just six games in all, averaged .292/.371/.545 at the plate, and won two Gold Gloves. Although he never led the league in a major offensive category, he finished in the top ten in home runs every year, and only once, in 1994, did he finish out of the AL RBI leaders.

Although Palmeiro has not played long enough in Baltimore to dominate the club leaderboards, he compiled an impressive string of achievements in his first go-around with the O's. During that run, he notched four of the top ten single-season home run totals in club history. His 182 home runs for the Orioles in that span tied Ken Singleton for sixth in modern club history. And he produced in the run department, too; if his stats from the strike-shortened seasons of 1994 and 1995 are extrapolated to a 162-game season, he would have cleared 90 runs and 100 RBI in every year he played as an Oriole. His 142 RBI in 1996 remain the club record for a single season, although Miguel Tejada is threatening that mark this year. Palmeiro's .545 slugging percentage from 1994 to 1998 led all Orioles with 2,000 or more plate appearances from 1954 to 2003, his 133 adjusted OPS+ was seventh, and his .312 EqA (normalized for era) was second.

Since his major-league career began in 1986, Palmeiro has gone about his business so quietly that even his own fans may not realize how great he has been. His production, in the context of his era, is just as impressive as Powell's and Murray's in theirs. Through 2003, Palmeiro's career batting line was .291/.373/.522. But, you say, this was during a high-offense era with the aid of hitter-friendly home parks. Yes, but after adjusting for those factors, his performance translated to a 134 adjusted OPS+ and a .313 EqA, numbers as good as or better than Murray's and Powell's. As Palmeiro's declining performance from 2004 and beyond is added to the record, those figures will go down slightly, but not much.

Best of the rest

Honorable mentions for top Oriole first basemen go to Jim Gentile (1960-1963), Randy Milligan (1989-1992), and Jeff Conine.

Gentile a giant, if only briefly

Gentile had one of the most potent seasons with the bat ever by an Oriole in 1961, posting a line of .302/.423/.646 with 46 home runs (third in modern Orioles history) and 141 RBI (second). His unadjusted slugging percentage and OPS that year were the highest single-season marks in modern Oriole history, his on-base percentage was the second highest, and his 32 Win Shares that year tied for the 10th best. Of course, that was the year that Maris and Mantle chased Ruth in the record books, so Gentile was relegated to third in the MVP voting.

Aside from that one astounding year, Gentile had productive seasons for the O's in 1960, 1962, and 1963, receiving All-Star nods from 1960 to 1962. He was a major reason for the Orioles going from a sub-.500 team to a pennant threat. But expectations were high after his 1961 season, and he didn't come close to matching that performance in 1962 and 1963, as his power numbers appeared to take a dive (although the raising of the pitcher's mound had a lot to do with that). So Baltimore traded him to the Kansas City A's for their first baseman, Norm Siebern, after the 1963 season.

The trade was a wash, as it turned out that both players were entering the sunset of their careers. Gentile played a year and a half for the A's before being traded to the Astros and again to the Indians the following year. He was just 32 when he played his last game in the majors in 1966. Siebern contributed two undistinguished seasons for Baltimore before he was traded again in 1965 to allow Powell, who had been playing left field less than brilliantly, to move to first base permanently. (The player the Orioles received for Siebern, Dick Simpson, a week later was redealt as part of the package to obtain Frank Robinson from the Reds.)

Due mainly to his astronomical 1961 performance and the fact that his four seasons for the O's came in his prime, Gentile ranks among Oriole career leaders in several offensive rate stats: on-base percentage (.379, 6th), slugging percentage (.512, 3rd), unadjusted OPS (.891, 3rd), adjusted OPS+ (143, 2nd), and EqA (.309, 5th). Gentile contributed enormous value for the Orioles when he was in the lineup; his 25.8 Win Shares per 162 games as a Bird edged out Palmeiro's 24.2 and Powell's 23.2 and barely trailed Murray's 26.4.

Because of Gentile's high level of performance, it was not an automatic call to place him behind Palmeiro in this ranking. But Palmeiro played five seasons in Baltimore compared to Gentile's four, and whatever Gentile had over Palmeiro in per-game production, Palmeiro gained back in consistency and durability (Gentile missed nearly 60 of the Birds' scheduled games over his four seasons in Baltimore).

The Moose (version 1.0)

Before Mike Mussina came onto the scene, the nickname Moose for Orioles fans meant Randy Milligan. Like Gentile, Milligan arrived in Baltimore as a late-blooming rookie (Gentile was 25 in 1960, Milligan 27 in 1989) and had a highly productive first few seasons in the majors before his output began to fade.

Milligan, who had proven himself at the minor-league level but was stuck behind incumbent major-league first basemen in two previous organizations, came to the Orioles in a seemingly minor swap of prospects in November of 1988. But when Murray was traded to the Dodgers the following month, Milligan immediately found himself in contention for the starting first baseman's job. He won the bulk of the work by being one of the Birds' most productive hitters in 1989, hitting for power (.458 SLG) and drawing tons of walks (74 in just 444 PA) to post an on-base percentage of .394, which would have been 11th in the league if he had accumulated enough plate appearances to qualify for the title. His 19 win shares that year helped the team execute one of the largest one-year turnarounds in history.

Milligan hit even better in 1990, clobbering 20 homers, drawing 88 walks, and producing a batting line of .265/.408/.492. But his season was cut short in early August when he separated his shoulder in a home-plate collision. Milligan's power numbers declined significantly after that incident. Over the next two seasons, he hit .263/.373/.406 and .240/.383/.361. But he continued to draw walks and get on base at a high rate, remaining a useful player even as the rest of his hitting game slipped. Milligan's manager, Johnny Oates, recognized the value of Milligan's on-base ability and continued to play him nearly every day despite the dropoff in his power numbers.

But at the end of 1992, the Orioles declined to tender Milligan a contract, forcing him to leave as a free agent. Though a popular player, he had been marginalized by the confluence of three factors: his waning performance, the Orioles' crowded situation at first base and DH, and the tight-fistedness of then-owner Eli Jacobs. (At first base, the Orioles had a young David Seguí ready for the majors, and the team was obligated to pay big money in 1993 to the injured Glenn Davis, whom the Orioles had acquired before the 1991 season in what became the most baneful trade in franchise history.) Milligan had a quality season in 1993 split between the Reds and Indians, then left the game after playing briefly in 1994. His .388 OBP for the Orioles ranks third in modern club history, and his .310 EqA, surprisingly, ranks fourth behind Murray, Palmeiro, and Frank Robinson.

Conine, steady as he goes

Jeff Conine is neck-and-neck with Milligan in Win Shares and WARP-3 earned as an Oriole. Milligan made a higher percentage of his contributions as a first baseman, however. During Conine's five-year stay with the Birds that ended with his trade to the Marlins in August 2003, he played 444 games at first base, but also saw significant action in the outfield, at third base, and at DH.

Though Conine was nomadic in the field, his Oriole career was marked by consistency at the plate. Conine's career batting line for the Birds was .290/.343/.449. In each of his seasons for Baltimore he hit from .273 to .311 and slugged between .438 and .460 with 13-15 homers and at least 20 doubles. His best year was 2001, when he hit .311/.386/.443 and contributed 24 Win Shares. Though none of his skills was outstanding, he provided yeoman service for the Birds during a down period in the club's history.

But there's no denying that Conine's baseball legacy is as Mr. Marlin, the only original member of the Florida expansion team to play for the 1997 and 2003 champions. That title may make it seem inappropriate to include him on a list of top Orioles of the last half-century, but it should not eliminate him from consideration entirely. It's debatable whether Conine deserves the fifth spot on this list ahead of Milligan, but he certainly deserves credit for having a productive career both in and outside of Baltimore.

Acknowledgements

Research for this article included statistics and transaction information from Baseball-Reference.com, BaseballProspectus.com, and Retrosheet.org. Of course, Bill James's book Win Shares supplied most of the Win Shares data, although I got 2002 Win Shares from BaseballTruth.com and 2003 Win Shares from Studes's Baseball Graphs. The Baseball Library also was a helpful resource for piecing together the player sketches.

Note: Future articles in this series will not be as extensive as this one because I'd like to complete the series by the end of the season as well as maintain some semblance of a life for the near future.

Next: second basemen.