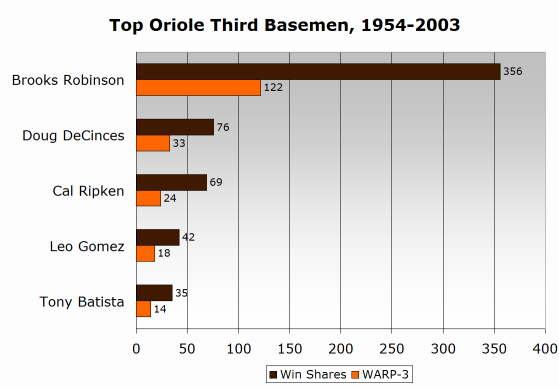

Top three third basemen in modern Orioles history:

- Brooks Robinson (1955-1977)

- Doug DeCinces (1973-1981)

- Cal Ripken Jr. (1981-2001)

Honorable mentions

Leo Gomez (1990-1995) and Tony Batista (2001-2003).

The contest for the top Oriole third baseman was no contest at all. Brooks Robinson finished so far ahead of the field in both Win Shares and WARP-3 that the only suspense was in the order of the runners-up.

Brooks: robbin' hits for the Birds for 23 years

During the first quarter-century after major-league baseball returned to Baltimore, no one better represented the Orioles on and off the field than Brooks Robinson. Signed by the club out of high school in 1955, Robinson saw big-league action that September, became a full-time player in 1958, and was a fixture in the organization until his retirement in 1977. In the intervening years he compiled hitting and fielding achievements that would fill an infinitude of pages in the team history and record books. A brief rundown:

- There is no question that Robinson's strength was his defense. Although he didn't have the most powerful arm for a third baseman, it was plenty accurate, and his hands, quickness, and anticipation were second to none. He was also ambidextrous, a gift that no doubt helped him with the exchange from glove to throwing hand. He reigns over all comers in the traditional fielding statistics for third basemen, leading the pack by wide margins in games played (2,870), putouts (2,697), assists (6,205), and double plays (618). He also has the best fielding percentage (.9713) of any third baseman with more than 1,000 games at the position.

- All of those exploits with the glove did not go unnoticed by his peers. Robinson took home sixteen Gold Gloves in his career from 1960 to 1975. In six of those years he accumulated the most defensive Win Shares in his league by a third baseman, so he certainly deserved a lot of that hardware, if not all of it. Admirers called him "The Human Vacuum Cleaner."

- Robinson was not a great hitter, but he was no pushover at the plate. When evaluating his offense, one needs to consider that he played his career in a pitcher-friendly park during a period when conditions were more hostile to hitters than they are now. His batting line of .267/.322/.401, when compared to the league averages of .253/.324/.383, was actually quite respectable in its context. His lifetime adjusted OPS+ was 104, and his era-adjusted Equivalent Average was .267. The baselines for those statistics are 100 and .260, respectively, so essentially Robinson was a step above a league-average hitter over his career.

- In his prime, Robinson was the American League's best third baseman. In addition to all those Gold Gloves, he posted an adjusted OPS+ better than the league average in ten out of the twelve seasons between 1960 and 1971 and was named to the All-Star team every year from 1960 to 1974.

- Robinson had a career year in 1964, batting .317/.368/.521 with 28 home runs, 35 doubles, and a league-leading 118 RBI. Although those figures look attainable for today's players, Robinson's performance that year was extremely impressive because it came during the era of the elevated pitching mound. The league averages were .256/.324/.397 in 1964, so Robinson's hitting that year was good for a 145 adjusted OPS+ and a .309 EqA (adjusted for era). Combined with his stellar fielding, that performance earned him 33 Win Shares, 10.1 Wins Above Replacement Player-3, and the American League's MVP award. He also finished in the top 10 in MVP voting six other times in his career.

- Robinson was also exceptionally durable, leading the league in games played in five seasons during the 1960s and finishing with 2,896 games played for his career, twelfth most in history.

- The combination of durability, longevity, and above-average hitting also helped Robinson attain some lofty career hitting totals. A table can illustrate these numbers far better than words, so here's one.

Brooks Robinson's batting totals and all-time ranks Category G AB H 2B 3B HR R RBI BB Brooks's total 2,896 10,654 2,848 482 68 268 1,232 1,357 860 Rank in O's history since 1954 2nd 2nd 2nd 2nd 1st 4th 2nd 2nd 6th Rank in MLB history through 2003 12th 13th 39th 57th 392nd 132nd 134th 69th 162nd - The Orioles made the postseason six times in Robinson's career, and he came through more often than not when the games mattered most. The pièce de résistance, of course, was his 1970 World Series MVP-winning performance against the Cincinnati Reds. In that series he was all over the field, stealing hits from Red hitters at seemingly every turn and hitting .429/.429/.810 with two homers, six RBI, and five runs scored as the Birds won the championship, four games to one. Robinson wasn't quite as deadly in the '69 and '71 Fall Classics, but his lifetime batting line in the playoffs and World Series was .303/.323/.462, a few ticks better than his regular season numbers.

Although Robinson lost his effectiveness as a player in 1975, no one really had the guts to tell him he was done, so he hung around a couple more years in a marginal role before bowing out in 1977. That year he became a charter member (along with Frank Robinson) of the Orioles Hall of Fame. In 1983, he was elected to baseball's Hall in his first year of eligibility.

Robinson is also one of baseball's all-around nice guys, loved by virtually all who have the fortune to know him. He is a model citizen who came to personify the Orioles, and to some extent the city of Baltimore, during the '60s and '70s. In retirement he has remained a visible icon in the Baltimore community; he was a commentator on Orioles games for the local on-air television affiliate until the mid-1990s, and he makes public appearances in the area from time to time. Robinson is a class act and without a doubt one of the greatest Orioles ever.

DeCinces: not Brooks, but not bad

The player cursed with the task of succeeding Robinson at third base for the Orioles was Doug DeCinces. After receiving big-league cups of coffee in 1973 and 1974, DeCinces began to earn significant playing time at the hot corner for Baltimore in 1975, and by 1976 he had effectively supplanted Robinson as the Orioles' starting third baseman.

The Baltimore fans were resistant at first to the idea of someone replacing their longtime hero, but DeCinces was actually a worthy successor when all things were considered. He was an able and steady fielder, though not a brilliant one, and he hit about as well as Brooks did in his prime, averaging .253/.323/.428 in 858 games as an Oriole for a .277 era-adjusted EqA. In 1978, DeCinces had an awesome year worthy of an All-Star nod (though he didn't get one), hitting .286/.346/.526 with 37 doubles, 28 home runs, and 80 RBI. His home runs, doubles, and slugging percentage led the team, and his adjusted OPS+ of 149 was sixth in the league.

But in the next three seasons Decinces's bat returned to more ordinary levels, and with a top third-base prospect named Ripken knocking on the door, at the beginning of 1982 the Orioles traded DeCinces and another prospect to the California Angels for outfielder "Disco" Dan Ford. That move didn't pan out so well, as Ford fell short of expectations, the top third-base prospect instead became an All-Star shortstop, and the team was left with a revolving door at the hot corner for the rest of the decade. Meanwhile, DeCinces rebounded with a monster year in 1982 for the division-winning Angels, hitting .301/.369/.548 with 30 homers and finishing third in MVP voting. Though he would not approach that level again, he contributed several respectable seasons for California before retiring in 1987.

Ripken comes full circle at third

I have done something for Cal Ripken that I have not done for any other player in this series of articles. That is, I have attempted to subdivide his career Win Shares and WARP-3 between each of the two positions he played in his career, shortstop and third base. (For other players who appeared at more than one position during their Oriole careers, I have listed them only at their primary position, expressing their Oriole Win Shares and WARP-3 across all the positions they played.) I changed the recipe for Ripken in part because his lengthy career separates somewhat neatly into two stages, the shortstop years (about half of 1982 plus 1983-1996) and the third base years (half of 1982 plus 1997-2001). But I also did it because of the dearth of viable third basemen in club history after Robinson and DeCinces. It's less than ideal, but it certainly reveals how good a player Ripken was (as well as how weak the Orioles' third sackers were after Robinson) that essentially the last quarter of his career was good enough to finish third in this ranking.

The story of Ripken's career is an epic one that I will tell in more detail in the shortstops article; here I will focus on his experiences as a third baseman. A tall, lanky youngster with a throwing arm strong enough for him to be considered as a pitching prospect, Ripken came up through the minors as a third baseman. As he moved up through the Orioles' affiliates, he was often flanked by Bobby Bonner at shortstop, and some observers thought that they would be starting at those positions someday in Baltimore. But it was not to be, as Bonner's weak bat held him back from a major-league role. Ripken began the 1982 season as the Orioles' starting third baseman, but midway through the season, manager Earl Weaver tried his young rookie at shortstop, thinking that Ripken's arm, soft hands, and sharp instincts would translate to the position. The experiment worked, and Ripken never went back—until 1996.

In '96, Davey Johnson was the manager, and he wanted to get a better look at infield prospect Manny Alexander at shortstop. So for about a week Johnson started Ripken at third and Alexander at shortstop. Unfortunately, Alexander's bat was about as bad as Bonner's, and his play in the field was not markedly better than the 36-year-old Ripken's. So after that failed audition, Ripken returned to shortstop for the remainder of the season.

But the Orioles decided that they needed to upgrade their infield defense for 1997, and in the offseason they signed shortstop Mike Bordick and gave Ripken the job at the hot corner. Ripken immediately became a good defensive third baseman, and he had solid years both offensively and defensively in 1997 and 1998. But his back was beginning to bother him, and back pain forced him to miss nearly half of the 1999 and 2000 campaigns before he called it quits after the 2001 season.

Ripken's hitting stats as a third baseman were not overly impressive; he ended up batting .269/.318/.426 in 675 games at the hot corner. Such production is superficially comparable to that of the two other finalists at this position. However, because most of Ripken's plate appearances as a third baseman came in the high-offense environment of 1997 to 2001, his performance relative to his peers should be downgraded a notch. Consequently, he rates as a league-average hitter in his days as a third baseman. He was elected the AL's All-Star starter at the hot corner five straight times from 1997 to 2001, but in most of those years his popularity with the fans gave him an advantage over well-qualified peers.

Honorable mentions

The best of the rest were Leo Gómez (1990-1995) and Tony Batista (2001-2003).

Gómez, believe it or not, was the longest-serving third baseman for the Orioles during the decade and a half between DeCinces and Ripken. He became a mostly full-time player in the early 1990s, taking up the slack for the similarly skilled Craig Worthington. A fair hitter, Gómez batted .245/.334/.414 in 475 games for the team, 446 of which came at third base. Although his batting average was subpar, he drew walks with some regularity and hit for some power. His fielding was unremarkable. After Gómez struggled at the plate in 1995, the Orioles let him leave as a free agent, and after a decent season with the Cubs he concluded his big-league career.

Batista, picked up off waivers from Toronto in June 2001, filled the hole created by Ripken's impending retirement. He flailed at pitches with a unique looping uppercut that resulted in several home runs, although his production was undermined by low batting averages and a conspicuous lack of walks. His batting line for the Orioles was .245/.293/.433. Batista was more conventional-looking in the field, where he provided steady, low-key play at the hot corner. Durability was never a problem for him, as he sat out just two games in his two full seasons with the O's after Ripken retired. But the Orioles revamped the left side of their infield after the 2003 season and sent Batista packing. He spent 2004 playing for Montreal.